Tuesday, November 18, 2008

Virginia on the needs of a child

Virginia Zabriskie: "I believe in education. I believe it is important for a child. Education is more important than love."

Why did Ralston Crawford return to study ships' masts at the end of his career, having seemingly exhausted the topic forty years prior?

His career was a steady trajectory-- beginning with what was inevitably lumped in with Precisionism and exploring the integration of the picture plane with a deepening disregard for depiction. He toyed with a lot of the issues of symbolic representation and the destabilization of purely symbolic forms -- stuff that Stuart Davis is known for -- by working and reworking anchors and boats and boxcars throughout his career. But the ships' masts weren't Picasso-by-way-of-Davis post-cubisms, nor were they precisionist by any standard. Apart from his lifelong devotion to the sea as a place of meditative calm, what more did he expect to wrench from this theme?

But the ships' masts weren't Picasso-by-way-of-Davis post-cubisms, nor were they precisionist by any standard. Apart from his lifelong devotion to the sea as a place of meditative calm, what more did he expect to wrench from this theme?

Barbara Haskell--whom I was apparently sitting near at the Mandarin Hotel a few nights ago--pointed out how differently Ralston's use of the the sky became after WWII. While he previously used it as a natural, vast flatness, there was always something a little phoned-in, as if the sky, a natural surface, could be activated merely by painting the canvas blue. Sometimes he daubed a little graceless, non-committal cloud over a highway to spruce things up-- but I don't think he really got it, the full activation of the plane, until...Bikini Atoll.

I don't know what pact he might've made with the almighty as Ralston watched the mushroom cloud spread over the Pacific, but I do know this: from that day forward, his skies had a presence in his paintings.

Witness Masts & Riggings of '72, up now at the gallery. Rather than trying to fill the space with brooding little thunderhead, he allows the asymmetric divisions of the sky to ring out as positive spaces, the lines and mast spider-webbing out like a broken windshield.

His career was a steady trajectory-- beginning with what was inevitably lumped in with Precisionism and exploring the integration of the picture plane with a deepening disregard for depiction. He toyed with a lot of the issues of symbolic representation and the destabilization of purely symbolic forms -- stuff that Stuart Davis is known for -- by working and reworking anchors and boats and boxcars throughout his career.

But the ships' masts weren't Picasso-by-way-of-Davis post-cubisms, nor were they precisionist by any standard. Apart from his lifelong devotion to the sea as a place of meditative calm, what more did he expect to wrench from this theme?

But the ships' masts weren't Picasso-by-way-of-Davis post-cubisms, nor were they precisionist by any standard. Apart from his lifelong devotion to the sea as a place of meditative calm, what more did he expect to wrench from this theme?

Barbara Haskell--whom I was apparently sitting near at the Mandarin Hotel a few nights ago--pointed out how differently Ralston's use of the the sky became after WWII. While he previously used it as a natural, vast flatness, there was always something a little phoned-in, as if the sky, a natural surface, could be activated merely by painting the canvas blue. Sometimes he daubed a little graceless, non-committal cloud over a highway to spruce things up-- but I don't think he really got it, the full activation of the plane, until...Bikini Atoll.

I don't know what pact he might've made with the almighty as Ralston watched the mushroom cloud spread over the Pacific, but I do know this: from that day forward, his skies had a presence in his paintings.

Witness Masts & Riggings of '72, up now at the gallery. Rather than trying to fill the space with brooding little thunderhead, he allows the asymmetric divisions of the sky to ring out as positive spaces, the lines and mast spider-webbing out like a broken windshield.

Friday, November 14, 2008

Evans/Crawford: Kindred Spirits

The reason I was studying Walker Evans will perhaps become clear (to you, to me) in 2009, but for the meantime, suffice it that Evans has been on the brain-- feverishly. And, of course, Ralston Crawford.

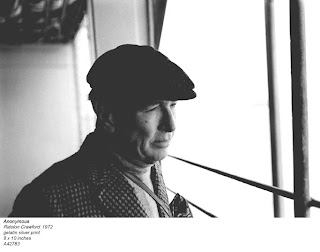

The reason I was studying Walker Evans will perhaps become clear (to you, to me) in 2009, but for the meantime, suffice it that Evans has been on the brain-- feverishly. And, of course, Ralston Crawford.Ralston Crawford's photos are often departure points. They find in the world a play of shadows and patterns that is ripe for abstraction, but Virginia is more-or-less right: "There is no such thing as abstract photography." (Yes, she has done a show entitled, "Abstraction in Photography"; more-or-less, you see...) And because Ralston believed that the step off into inventing one's own abstractions was strictly out-of-bounds, his paintings are littered with the debris of depiction, and with a careful eye and the aid of his preparatory sketches and photos, you can wend your way back to the thing itself. It's a fun path, and it's lovely walking both ways: the paintings lend themselves to decoding, the photos lend themselves to ciphers.

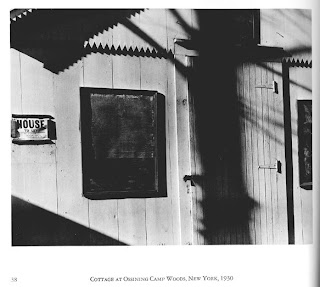

Walker Evans, had a sort of hard line against this. The things themselves oughtn't be drenched in style-- John Szarkowski writes (in the 1971 MoMA monograph) that "Nothing was to be imposed on experience; truth was to be discovered, not constructed. It...freed...him from too solicitous a concern for the purely plastic values that were of central importance to modern painters." (p. 12-13) And the pictures tell it straight: as in, fully frontal, buildings that look like buildings, signs that look like signs, people that look like people. The artiness of Stieglitz eschewed, the flatness of the Bechers prefigured. See a picture of a house, page 39 of the MoMA monograph: If any mystery remained, it is clearly labeled with a sign. The sign says, "HOUSE." Get it?

I've been eating, breathing, sleeping and dreaming Ralston Crawford for the last month, and the instant I saw this picture I thought about how Ralston would have cropped in on the middle left side of the house and shown the patterns of shadows as semi-abstract blacknesses. The house would be there-- even the word "House," but in a Crawford photo, they'd've been reduced (or promoted?) to abstract formal qualities. "But Walker," I thought, "would have lost his lunch over such saccharine 'design elements.'" Then I turned to the next plate:

Walker Evans, closet Crawfordite!

Is this thing on?

Virginia Zabriskie, proud gallerist, and recent recipient of the Archives of American Art's annual medal of honor, drummed her fingers nervously on the desk. In the office almost every day for 52 years might've taken off some of the edge, but there it was again today: the worry that no one will come. Of course we're optimistic, and the lousy economy is hurting almost everyone worse than the gallery, but 3:00 felt pointedly slow today.

"How are we going to get people in here to see this beautiful show?" she asked.

I turned back to my computer. The needs of a gallery are ceaseless, but the owner, indefatigable, wants answers. There will never be a satisfactory amount of foot traffic, even if the place is packed 8 hours a day.

"Why don't I write a gallery blog?" I said, without turning. "You know, create a buzz. Raise our profile on the internets. Information superhighway."

"A buzz?"

"Houk's got one." A buzz? Possibly. A blog? Certainly not.

"What will it cost us?"

"Not a red cent."

"Well, ok. Then I'd say do a couple of gallery blogs."

Roger that, I think. And now I give you...the buzz!

Up now at the gallery: Ralston Crawford, in its last week:

Crawford, popularly known for his paintings, found inspiration in industrial and seafaring scenes. His flattened arrangements of space approached abstraction with a firm belief in working from life rather than imagined geometries.

After a short stint painting animation cells for Disney, Crawford’s artistic training began in earnest at the

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)